I Didn’t Understand Chapter 2 Until I Wore the Gown

- La Chambre Bleue

- 4 days ago

- 4 min read

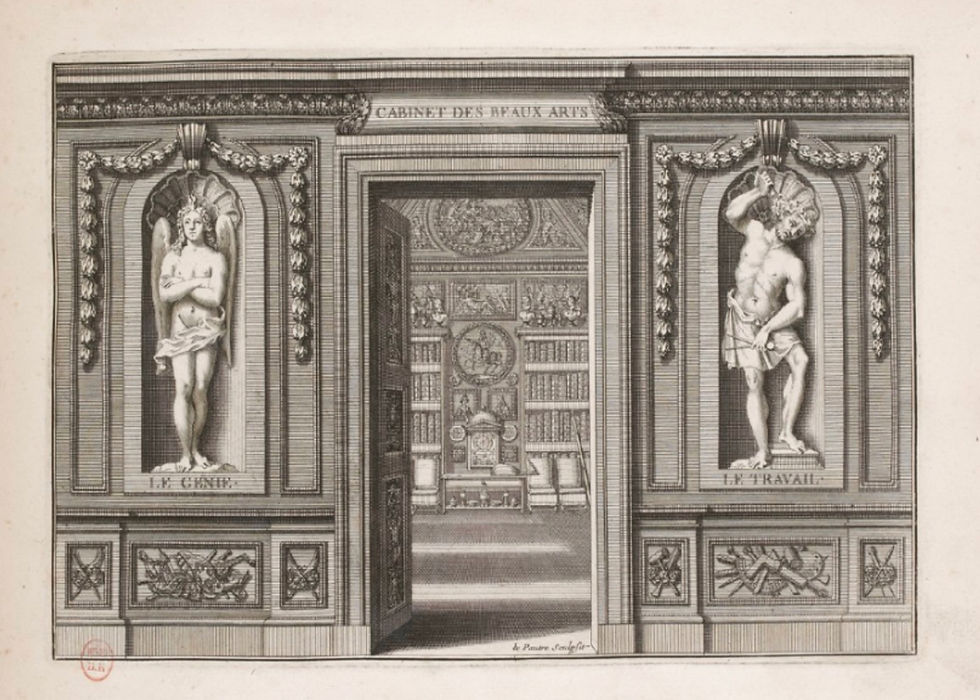

Illustration for Cendrillon by Charles Perrault. Unknown illustrator, 1697.

Honnêteté, Women, and Knowing Through Appearance

There is a moment in research when an argument stops being purely conceptual and becomes embodied. For me, Chapter 2 of my work on Perrault did not fully resolve until I stood at Versailles—moving through its spaces, studying its surfaces, and thinking seriously about what it meant, in the seventeenth century, to appear.

In Cinderella, the heroine is accepted into society and her worth is recognized based upon how she appears at the ball. What do we make of this emphasis on surface and appearance? In my research, I found a thread linking women across Perrault’s poetic and critical works: Cinderella (1697), the Nymph of Painting in La Peinture (1668), the Learned Lady and the bourgeois wife of the Apologie des femmes (1694). At first glance, these women seem fundamentally unrelated. They differ in class, education, authority, and sphere of action. Some speak publicly; others govern privately. Some inspire gods; others raise children.

And yet, Perrault binds them together through a single ethical and aesthetic principle: honnêteté.

The Royal Apartments. 2019 Fête Galante. Versailles. Photo credit: Jennifer Davis Taylor

Honnêteté Is Not Silence

Modern readers often encounter early modern femininity through caricature: women as silent, decorative, or morally constrained. But Perrault is drawing on a far more complex moral tradition. In L’honnête femme (1632), Jacques Du Bosc defines a woman whose virtue is active, cultivated, and intelligent. She reads. She reasons. She converses well. She develops judgment through the study of history and philosophy. This is not a figure whose virtue depends on ignorance or withdrawal from the world. She is someone playing her part on the world stage, her body conversing with her space as in the photograph above.

Du Bosc is explicit that women’s silence is not a moral ideal. Instead, the honnête femme regulates herself through discernment. She avoids vice not by disappearance, but by occupying herself with useful and worthy pursuits, and by maintaining conduct that does not give rise to gossip or scandal. Importantly, Du Bosc insists that honnêteté is not a matter of noble birth. It is acquired through education and practice and is therefore grounded in personal merit. Du Bosc was not the only theorist of women's behavior. However, his attitude seems closest to how Perrault depicts various female characters.

This stance or one very similar is what allows Perrault to extend honnêteté across class lines. The Nymph of Painting and the Learned Lady are aristocratic, learned, and culturally authoritative. They are makers of cultural capital. The bourgeois wife of the Apologie is neither a salonnière nor a public intellectual. And yet she, too, embodies honnêteté—expressed through economy, patience, moral steadiness, and the governance of domestic life. In the Early Modern Society of Orders in France, honnêteté was expressed through appearance and behavior according to one's class. It was based upon integrity--upon the principle that the outside reflected the inside, and the inside could be perfected within these social strata.

Therefore, what links these women is not social position, but a shared ethical posture: self-mastery, good judgment, modesty without erasure, and a capacity to orient others toward harmony.

At the 2019 Fête Galante. Versailles. Photo credit: Jennifer Davis Taylor

Civility Is Born in Women’s Company

Perrault is remarkably direct about the social function of women. In the Apologie, he claims that civility itself is born in women’s company and cultivated through their presence. He illustrates this by contrast: the man who lives without women becomes coarse, linguistically crude, physically unkempt, and incapable of refinement. Removed from female society, he loses access to taste, grace, and proportion. Exposure to honnête femmes of any social tier disciplines men’s gestures, speech, and judgments. It teaches balance: boldness without vulgarity, freedom without cruelty, wit without malice.

This is not a sentimental praise of women’s charm. It is a structural claim about culture. Honnêteté is not self-generated. It is learned relationally—and learned, above all, from women.

Taste as Authority

This logic extends decisively into Perrault’s thinking about art and criticism. In the Parallèle des anciens et des modernes, Perrault invokes women’s judgment as authoritative in matters of taste. In one telling anecdote, a lady’s distaste for a recent translation of Pindar’s Odes becomes evidence against the superiority of ancient literature. The Abbé, Perrault’s mouthpiece, insists that women are particularly sensitive to what is clear, lively, natural, and well-proportioned—and quick to reject what is forced, obscure, or tiresome.

What matters here is not proof in the modern sense. As Jacqueline Lichtenstein has observed, Perrault does not argue by demonstration but by distaste. Authority lies in the shared law of propriety—the ability to feel when something is excessive, awkward, or falsely elevated. This authority governs words, gestures, and artworks alike, and it is acquired through social practice rather than abstract reasoning.

Good taste and honnêteté are thus inseparable. Both are grounded in judgment, balance, and self-restraint. And in Perrault’s account, both find their source in the society of women.

Wearing the Gown

It was only when I stood at Versailles—thinking about fashion, ceremony, space, and Cendrillon—that I fully grasped what was at stake in this chapter. Perrault’s ethics cannot be understood without attending to appearance. Not appearance as deception, but appearance as method and theatre.

To dress the part, in Perrault’s world, is not simply to perform status. It is to inhabit a moral and aesthetic order. Honnêteté is worn and inhabits proportional space. It shapes posture, speech, judgment, and relation. It is learned through the body as much as through the intellect.

This realization clarified the chapter’s methodological claim. Perrault is not only making an argument about women, art, and virtue. He is offering a way of knowing—one that refuses to separate ethics from aesthetics, or judgment from embodiment.

I didn’t understand Chapter 2 until I wore the gown—because Perrault teaches us that knowledge, like culture itself, is made where appearance, relation, and moral discernment meet.

At the 2019 Fête Galante. Versailles. Photo credit: Jennifer Davis Taylor

Comments