The Room that Spoke: Charles Perrault's Cabinet des Beaux Arts

- La Chambre Bleue

- Dec 8, 2025

- 2 min read

Updated: Dec 9, 2025

In 1690, Charles Perrault published a book so unusual that it demanded more than a reader—it required a visitor.

Le Cabinet des Beaux Arts is not simply a text. It is a three-dimensional intellectual interior. Designed as the artistic heart of a private home, the Cabinet offers itself as a total environment—one that fuses word and image, allegory and architecture, intimacy and ideology.

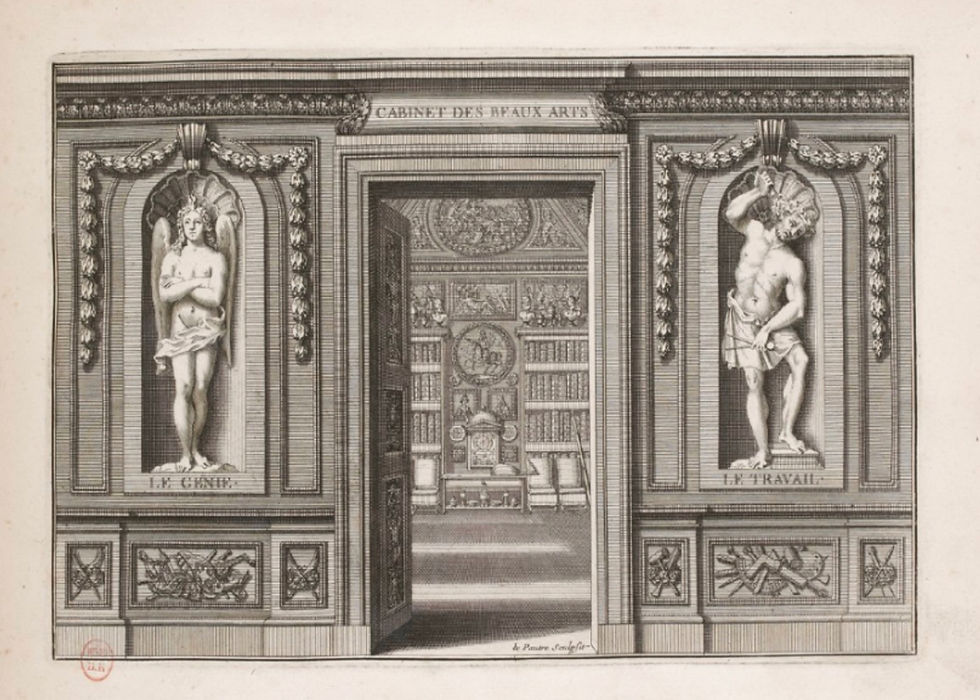

"Doorway to Le Cabinet." Pierre Lepautre, engraver. In Le Cabinet des Beaux Arts. 1690. [p. i]

Upon entering, we are greeted by a symbolic doorway: flanked by statues of Genius and Hard Work, the threshold opens into a richly appointed study where a telescope waits. The device invites us to look upward—at the allegorical ceiling—but also places us in view of the gods. From the floor, the telescope is a link to heaven; from above, it becomes a microscope through which the divine observes human endeavor. This duality captures Perrault’s core proposition: that beauty arises when earth meets sky, raw nature meets refined mind.

Ceiling Design for Le Cabinet." Jean Dolivar, engraver. In Le Cabinet des Beaux Arts. 1690. Between p. 1 & 2.

As a designed environment, the Cabinet becomes an allegory of France itself—Louis XIV’s sun at the center, the fine arts blooming like flowers under his radiant gaze. Apollo presides above, and below him, along the ceiling’s edge, the Muses array themselves not hierarchically, but relationally. Poetry, Music, Eloquence, Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, Optics, Mechanics—all are linked by resonance, not rank.

This structure resists linear narrative. Instead, it asks us to wander—to experience associative movement and juxtaposition, like a visitor drifting through a salon, engaging where one is drawn. It is a physical metaphor for intellectual freedom under royal order: controlled, but not constrained.

Perrault, writing as both theorist and practitioner, does not stop at designing an interior space. His engraved book documenting the project with prose descriptions and poetic interpretations of each painting introduces engraving as the ninth art—the one that binds and extends all others. Here, engraving isn’t reproduction. It is completion and extension of the built environment.

Even the paratext participates in this rhetorical design. Historiated capitals, mottos, and dedications signal the emotional logic of the work. “Solis Amans”—the lover of the Sun—hints that love, not reason, fuels this system.

Reproduction of Historiated Capital from dedication letter [Gerard Edélinck, engraver]. In Le Cabinet des Beaux Arts. Edélinck, 1690. [p. ii]

From the Corinthian maiden who traces her lover’s shadow to the silk-stocking machine said to have been invented by desire, we are reminded that Love animates both the "lowest" of mechanical arts and the metaphysical imagination engaged in eloquence and poetry. In Perrault’s cabinet, even engineering has an erotic origin.

This is a room that spoke—and still speaks.

It murmurs: step inside.

Comments